The operating room is a world of sterile fields and standardized protocols. But the patient on the table? They bring a whole universe with them. A universe of beliefs, values, languages, and traditions that profoundly shape their experience of illness, healing, and trust.

Honestly, providing top-tier surgical care today is about more than just technical skill. It’s about cultural competence. It’s the critical, often overlooked layer that can mean the difference between a patient who feels heard and healed, and one who feels alienated and afraid. Let’s dive into why this matters and how it works in practice.

Beyond language barriers: The true scope of cultural competence

Sure, when we think of cross-cultural care, professional medical interpreters are the first, non-negotiable step. They’re not a luxury; they’re a safety requirement for informed consent and accurate history-taking. But true cultural competence in a surgical setting goes way, way deeper than just words.

It’s about understanding the why behind a patient’s actions. Why a family might refuse a blood transfusion. Why a patient may be hesitant about pain medication. Why an elder might not look you in the eye. These aren’t just quirks; they are expressions of deeply held cultural and spiritual values.

Key areas where culture impacts surgical outcomes

Culture weaves itself into nearly every facet of the patient journey. Here are some of the most critical touchpoints.

Communication and decision-making styles

Not every culture prizes the individualistic, “patient-as-autonomous-decision-maker” model that is standard in many Western healthcare systems. In fact, in many parts of the world…

- Family-centric decision-making is the norm. A patient may expect to consult with a large family group, or defer entirely to a senior family member. Pushing for an immediate, individual decision can create immense distress and break trust.

- Indirect communication is preferred. A patient may say “yes” to indicate they understand you, not that they agree with the plan. Or they may avoid saying “no” directly out of respect for your authority.

- Non-verbal cues are paramount. Eye contact, gestures, and personal space all carry different meanings. A patient’s silence might signify contemplation, not confusion.

Beliefs about illness, pain, and the body

Where does disease come from? Is it a biological glitch, a spiritual imbalance, or perhaps a consequence of past actions? A patient’s explanatory model for their illness directly influences their acceptance of treatment.

Some cultures have specific beliefs about body integrity. The removal of an organ or limb might be seen as rendering the person incomplete in this life—or the next. Some may have strong preferences about who can see or touch their body, especially concerning gender. A simple request for a same-gender provider, when possible, isn’t a preference; it’s a profound need for dignity.

Diet, fasting, and spiritual practices

Pre-operative fasting is standard, but what if a patient is also observing a religious fast? Or what if their faith requires specific prayers at specific times, or the wearing of a sacred item? I’ve seen the panic in a patient’s eyes when they’re told they must remove a religious thread or medal for surgery. A little foresight—sealing it in a sterile pouch, for instance—can preserve both safety and soul.

Practical strategies for a culturally competent surgical practice

Okay, so this is important. But how do you actually do it in the high-stakes, fast-paced surgical environment? It’s about building systems, not just relying on good intentions.

1. The pre-operative assessment: Dig deeper

Your nursing and anesthesia teams are on the front line. Integrate cultural assessments into the pre-op checklist. Go beyond “Any allergies?” and “Do you smoke?” Ask open-ended questions like:

- “Are there any cultural or spiritual practices that are important for us to know about during your stay?”

- “Is there anything we should know about who makes health decisions in your family?”

- “Do you have any specific beliefs about blood transfusions, pain, or anesthesia that we should discuss?”

2. Informed consent as a process, not a form

That signed piece of paper is a legal document, sure. But the process of getting there is a cultural exchange. It requires checking for understanding in a way that transcends language. Use the “teach-back” method. Ask the patient to explain the procedure back to you in their own words. Watch their body language. Involve the interpreter and the family, if that’s the patient’s wish.

3. Navigating religious & spiritual objections

Certain scenarios require particular sensitivity. Let’s look at a couple of common ones.

| Scenario | Potential Cultural/Religious Link | Actionable Steps |

| Refusal of Blood Transfusion | Jehovah’s Witness beliefs based on biblical interpretation. | Engage early. Discuss blood-saving strategies (iron therapy, cell salvage technology) pre-operatively. Ensure consent forms are meticulously detailed. |

| Request for Amputated Limb | Some Indigenous, Buddhist, or other traditions may believe the body must be whole for the afterlife. | Coordinate with the pathology department and family for the respectful return of the body part, following specific rituals if requested. |

The human and the hospital: Making it work

This isn’t about memorizing a checklist for every culture on earth—that’s impossible. It’s about cultivating a mindset of humble curiosity. It’s about shifting from asking “What is wrong with this patient?” to “What matters to this person?“

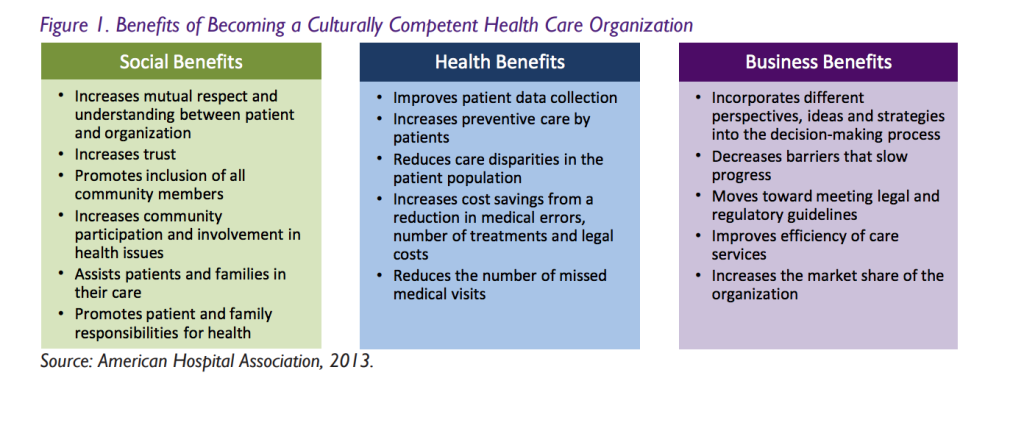

The modern healthcare landscape, with its focus on patient satisfaction and reducing disparities, is finally catching up to this reality. Hospitals are investing in interpreter services, staff training, and community liaisons. But the most powerful change happens at the bedside, in the pre-op room, in the way a surgeon pauses to truly listen.

That pause, that question, that moment of respect… it’s not a delay in the schedule. It’s the foundation of a therapeutic alliance. It’s the bridge between the cold steel of a scalpel and the warm, beating heart of the person trusting you with their life. And in the end, that trust might just be the most powerful medicine in the room.