Let’s be honest—the world of teen plastic surgery is a minefield of emotions, ethics, and evolving identities. It’s not the same as an adult walking in for a consultation. The stakes feel higher, the motivations more complex. And the ethical responsibility? It’s immense.

Here’s the deal: when a teenager expresses a desire to change their appearance through surgery, it’s rarely just about the nose or the ears. It’s often tangled up in self-esteem, social media pressure, and the brutal process of simply growing up. So, how do we navigate this? The answer lies in a consultation process built on a foundation of deep ethical consideration, not just clinical assessment.

The Core Ethical Pillars Every Consultation Must Rest On

Think of an ethical teen surgery consultation like a three-legged stool. Knock out one leg, and the whole thing collapses. These pillars aren’t just nice-to-haves; they’re non-negotiable.

1. Assessing Psychological Readiness & Motivation

This is, without a doubt, the most critical step. Is the desire coming from the teen, or from external pressure? A surgeon’s job here is part detective, part psychologist. They need to listen for the difference between “I’ve been bullied about my nose for years” and “I want to look like this TikTok filter.”

Key questions that need to be asked—and truly heard—include:

- Who is driving this decision? Is it the teen, a parent, or a peer?

- Are expectations realistic? Surgery isn’t a magic wand for life’s problems.

- Is there an underlying body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)? Surgery can actually worsen BDD, a condition that requires psychological care, not a scalpel.

2. The Crucial Role of Parental Involvement & Consent

In most places, teens can’t consent to elective surgery on their own. So parents are gatekeepers, but they should be informed, thoughtful ones. The ethical practitioner creates a space for a three-way conversation, not a two-against-one dynamic.

Sometimes, honestly, the ethical move is to guide a parent away from pushing a procedure the teen seems ambivalent about. The goal is aligned, informed consent from both parties, with the teen’s autonomy at the center.

3. The “Cooling-Off” Period & Managing Expectations

Teenage impulses are… well, teenage impulses. An ethical safeguard is mandating a significant waiting period—often several months—between the initial consultation and the surgery date. This isn’t a punishment. It’s a buffer for reflection, to ensure the desire is persistent and not a passing trend.

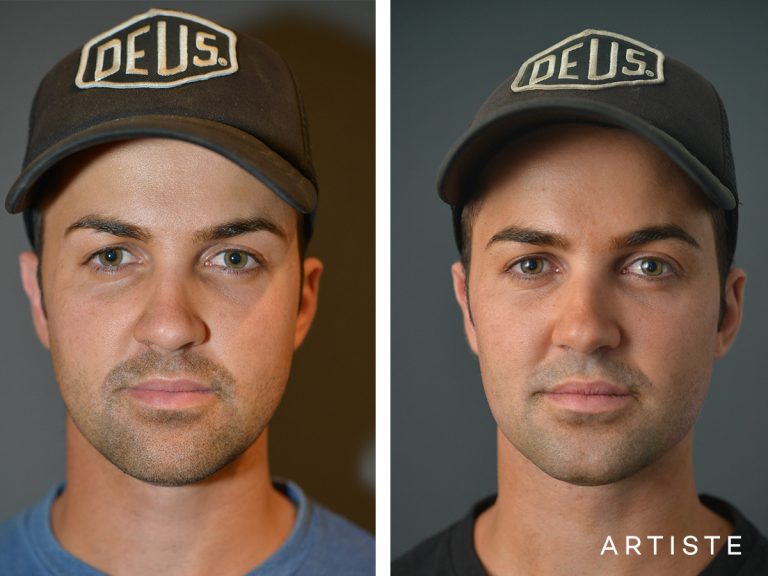

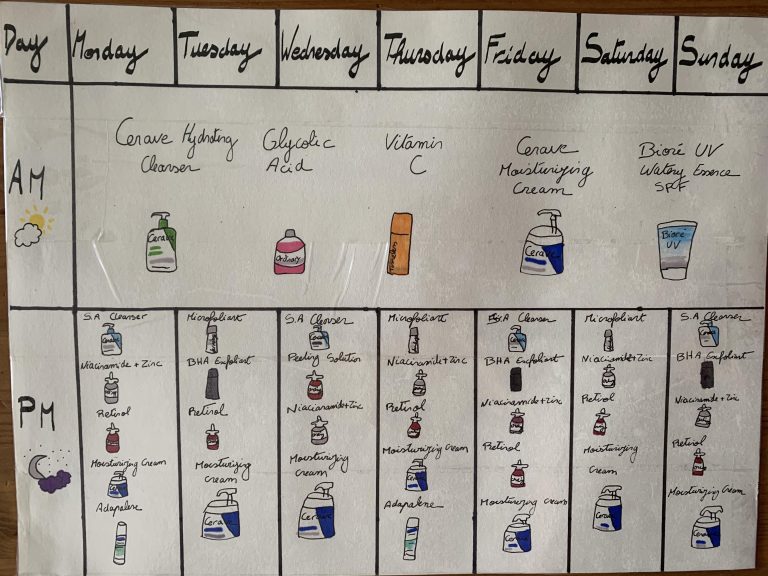

During this time, managing expectations through visual aids (like morphed photos, not filtered ones) and frank discussions about risks, scarring, and recovery is paramount. It’s about painting a real picture, not a fantasy.

Navigating the Modern Pressure Cooker

We can’t talk about ethics without acknowledging the elephant in the room: social media and the trend of “preventative” or “aesthetic” procedures for younger and younger patients. The rise of “Snapchat dysmorphia”—where teens want to look like their filtered selves—is a real, documented phenomenon.

An ethical consultation has to address this head-on. It might sound like: “I understand you don’t like this feature. But let’s talk about why, and whether changing it will change how you feel when you look in the mirror, or just how you look on a screen.” It’s a tough conversation, but a necessary one.

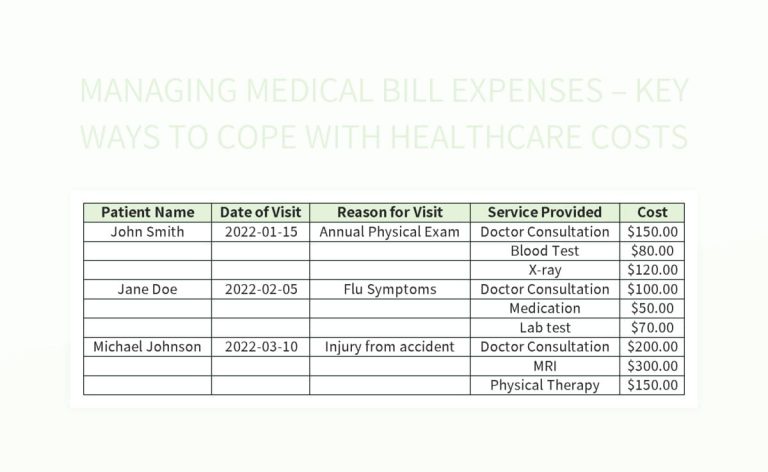

A Quick Guide: Ethical vs. Unethical Consultation Red Flags

| Green Flags (Ethical) | Red Flags (Concerning) |

| Surgeon asks “why now?” and explores emotional history. | Surgeon immediately agrees to the requested procedure without probing. |

| Discussion of non-surgical options first (e.g., dermatology, orthodontics). | Pressure to book surgery quickly, with “limited time” discounts. |

| Mandatory psychological screening for certain procedures. | Using only heavily edited or filtered “after” photos as examples. |

| Clear, detailed discussion of long-term risks and future revisions. | Minimizing recovery time or potential complications. |

| A comfortable, non-judgmental environment for the teen to speak. | The teen is silent while the parent does all the talking. |

The Surgeon’s Moral Compass

At the end of the day, the buck stops with the practitioner. They hold the medical license and the ethical duty. Sometimes, the most ethical action is to say “no,” or “not yet.” It takes courage to turn away a paying client, but protecting a young person’s physical and psychological well-being is the ultimate professional—and human—obligation.

This isn’t about being anti-surgery. Procedures like otoplasty (ear pinning) for a severely bullied child or rhinoplasty for a breathing impairment can be genuinely life-changing. The line is drawn at intention, at thoroughness, and at putting the whole patient first.

So, where does that leave us? In a place of careful, compassionate nuance. The journey of teen plastic surgery consultations isn’t a transaction; it’s a collaborative, cautious exploration. It asks everyone in the room—teen, parent, surgeon—to look beyond the surface and question not just what can be changed, but what should be, and why. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s well-being.